Lessons From 1879, When the Government Almost Shut Down but Didn’t

As clocks across Washington, D.C., struck 1 on the morning of March 4, 1879, the Capitol bustled with activity. Sleepless tourists packed its halls; Cabinet secretaries stayed huddled in consultation with congressmen; diplomats and socialites remained shoulder-to-shoulder in the Senate viewing gallery, transfixed by the scene unfolding below them.

They were all witnessing a grimly fascinating event—one that few Americans had, until that moment, thought possible: Their government was about to run out of money. More startling, the reason for its insolvency was not some economic crisis, nor war, but a deliberate act of sabotage. For the first time, one party had decided to withhold federal funding in an attempt to extort policy change from the other.

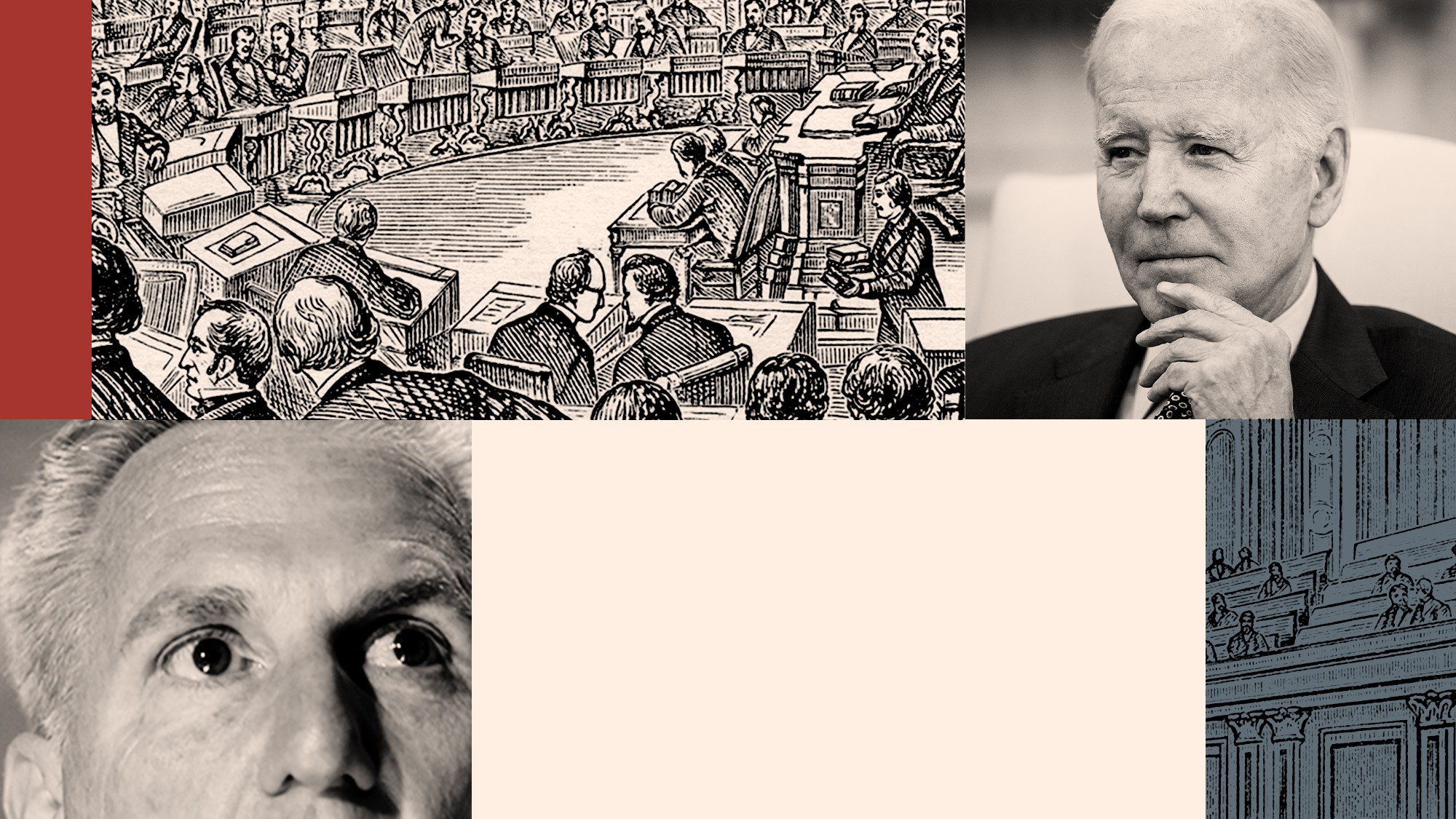

Modern Americans have grown tragically accustomed to party politics interrupting the core functions of government. Federal shutdowns seem to come and go like bad-weather events. President Joe Biden and Speaker Kevin McCarthy are currently sparring over what it will take for Congress to raise the nation’s debt ceiling so that we don’t default on our debts. That is what makes the country’s first self-inflicted funding crisis so fascinating: In the events informing the almost-shutdown of 1879—and the force that eventually resolved it—are lessons that might help us snap out of what has become an awful national habit.

The possible 1879 shutdown was devised with a particularly nefarious policy goal in mind. The House was controlled by the Democratic Party, whose representatives wanted to force Republican President Rutherford Hayes to yield what remained of Black voting rights in the post-Reconstruction South. To achieve this, they attached “riders” to crucial funding bills in the spring of 1879—addendums explicitly banning federal troops from monitoring southern polling sites against violence or fraud. When Hayes refused to sign these, Congress adjourned on March 4 without having passed sufficient funds for the government to operate. The president was forced to immediately summon a special session.

The battle had been met, but already its outcome was essentially decided. The Democrats’ unprecedented attempt to use their budgetary influence to secure policy change was doomed to fail, for three reasons.

The first was the president’s refusal to come to the bargaining table. From the onset of the funding standoff, Hayes expressed outrage at both its goal (as a friend had explained to him: to help Democrats “kill with impunity so many negroes as … to frighten the survivors from the polls of the South”) and its brazenness. He ruled out any compromise, promising to veto any new funding bills containing the riders. “It will be a severe, perhaps a long contest,” he wrote. Still, Hayes continued, “I do not fear it. I do not even dread it.”

The second reason for the shutdown’s futility presented itself after Hayes’s announcement. Now confident in White House support, House Republicans—led by future President James Garfield—developed an aggressive floor plan aimed at publicly confronting Democrats for gambling with the economic and social well-being of the country.

Garfield’s March 29 House speech launching this strategy shocked even Republicans with its vigor. Arms waving, the minority leader spent an hour accusing Democrats of treason for taking the government fiscally hostage. Garfield was a famously mild-mannered presence in Congress, but he could not contain his fury at the abuse of procedural power on display. He decried it as a potential deathblow to the country:

The House has today resolved to enter upon a revolution against the Constitution and government of the United States … the Democratic Representatives declare that, if they are not permitted to force upon the other house and upon the Executive, against their consent, the repeal of a law … this refusal will be considered sufficient ground for starving this government to death. That is the proposition which we denounce as revolution. On this ground we plant ourselves, and here we will stand to the end.

The effect was immediate. Garfield’s speech sent some Democrats scurrying to tell journalists that they didn’t support the shutdown. Others persisted in passing funding bills with the offensive riders attached, but President Hayes fulfilled his promise to veto these. Ultimately, though, the final and most important reason America’s first federal shutdown failed was that citizens were appalled by it.

Bankers publicly decried the impact of the crisis on “the business interests of the country.” Voters buried Democratic congressmen with letters and petitions demanding an end to the nonsense. Most devastating, America’s early comedians had a banner season; all through the spring, major papers ran joke columns about the partisan tail-chasing in Congress (“The dessert always reminds me of the veto, because it is the last thing on the bill”).

Eventually, House Democrats got the message. A freshman from Texas joined their caucus in June. New colleagues asked whether voters had elected him to add “backbone” to the shutdown fight. No, he solemnly replied, the people wanted not backbone, “but brains” in Congress for a change.

Democrats caved by late June, passing funding bills that mostly contained only scaled-down, meaningless riders. These Hayes duly signed into law. “Was there ever anything more ridiculous?” the secretary of state harrumphed as things in Washington finally got back to normal.

Modern Americans can answer this question with an embarrassed “yes.” What was once dismissed as absurd has been normalized. Though the issues at stake have changed, Garfield’s warnings of a future wherein Congress can abuse its power of the purse to “starve” the rest of government for policy concessions have been validated. It is almost certainly a reason Americans mistrust government (and Congress in particular) more than ever.

So long as officeholders of either party continue to view budget standoffs as possible political boons, all Americans suffer. Fortunately, the parable of 1879 shows how this “new normal” might be reversed—if enough citizens commit themselves to leading the charge.

We certainly have more ways to do so than ever before. Business leaders can get on television to communicate the dire economic consequences of petty political fights—as they recently have. Through social media, average Americans can focus their frustration directly on fiscal saboteurs in the House. Humor—whether from late-night hosts or TikTok stars—can “go viral” in a way that 19th-century columnists would only marvel (and probably grimace) at.

In the long run, though, ending the politics of fiscal sabotage will still require Americans to take their dissatisfaction with it to the ballot box, as we have before. There is something comforting in that.