How US Newspapers Became Utterly Ubiquitous in the 1830s

American newspapers of the 1830s were a distant, though recognizable, ancestor of the print medium we would come to know as a professional news-gathering operation. They had played a key role during the colonial period and war against England as a force for rallying pro-independence sentiment, with printers such as Samuel Adams employing the columns of their news sheets to excoriate the British (often with exaggeration) and to stoke the fires of rebellion. By the time of the country’s birth, the hook was set—Americans were a nation of committed newspaper consumers.

A high rate of literacy, especially in New England, and the movement of people from farms to towns and cities helped spur Americans’ thirst for news during the following decades. They read together in the home. They pooled money with neighbors for subscriptions and passed the papers back and forth. They retired—the men, at least—to the tavern, which stocked newspapers, and thus doubled as watering hole and reading room. In churches, ministers read the news to their seated parishioners. Even as early as 1822, historian Daniel Walker Howe notes, the United States led the world in the number of newspaper readers, regardless of population.

Newspapers were such a prominent feature of American life that foreigners from Europe who visited the young republic saw in it a phenomenon unlike anything back in the Old World. “The influence and circulation of newspapers is great beyond anything ever known in Europe. In truth, nine-tenths of the population read nothing else,” wrote Scottish writer Thomas Hamilton, who arrived in 1830. “Every village, nay, almost every hamlet, has its press.” Unlike books, Hamilton reported in a two-volume travelogue called Men and Manners in America, “newspapers penetrate to every crevice of the Union. There is no settlement so remote as to be cut off from this channel of intercourse with their fellow-men.”

Tocqueville, the French writer who was traveling the United States at around the same time, saw American newspapers as both silent counselor and social glue. “Nothing but a newspaper can drop the same thought into a thousand minds at the same moment,” he wrote. “A newspaper is an adviser who does not require to be sought, but who comes of his own accord, and talks to you briefly every day of the common weal, without distracting you from your private affairs.” Tocqueville added that “if there were no newspapers, there would be no common activity.”

Despite the noble-sounding talk about the ideals of democracy, American newspapering by 1830 also was a rough-edged trade, often practiced by not-very-educated men and frequently in the service of narrow political ends. Scholars politely refer to the phase of American journalism as the era of the “party press,” when most newspapers had a strongly partisan bent or were sponsored financially by one political party or the other and treated as its mouthpiece. Newspaper editors also worked as commercial printers—among the potential spoils of a party’s electoral victory were its governmental printing contracts.

The parties of the post-independence era had by the 1820s broken apart and morphed into two new groupings, the Democrats of Andrew Jackson and the National Republicans, later known as Whigs, who were affiliated most prominently with Lovejoy’s man, Henry Clay. Both parties employed networks of newspapers and editors as part of their nationwide machinery. (Jackson-aligned papers played a big role in getting him elected president in 1828, and two of the editors involved—Amos Kendall and Duff Green—would join the Jackson administration as advisers in his “kitchen cabinet.” Jackson, a keen practitioner of patronage, later named Kendall to the powerful position of postmaster general.)

Newspapers were such a prominent feature of American life that foreigners from Europe who visited the young republic saw in it a phenomenon unlike anything back in the Old World.Hamilton, the Scottish writer, was unimpressed with the practitioners of this style of partisan journalism. “The conductors of these journals are generally shrewd but uneducated men, extravagant in praise or censure, clear in their judgment of everything connected with their own interests, and exceedingly indifferent to all matters which have no discernible relation to their own pockets or privileges,” he sniffed. Tocqueville was even more blunt: “The journalists of the United States are usually placed in a very humble position, with a scanty education and a vulgar turn of mind.”

An opinion-oriented press required editors with, well, opinions—not to mention the writing chops that would be sufficient to engage in what Tocqueville said was their core job: “an open and coarse appeal to the passions of the populace.” In real life, this translated into a form of journalism that was often harsh, disparaging, and startlingly personal. Editors of the era debated each other—and the politicians they backed—through the pages of their papers, hurling insults and threats from one week’s edition to the next, often laced with healthy dollops of outright falsehood. Amid such intense partisanship, big-city editors faced off against each other in fistfights in the 1830s. James Watson Webb of the New York Courier and Enquirer fought two rival editors and attacked a third—three times—on the streets of New York. In the country’s opening decades, several disputes arising from the news pages ended up in duels. Journalism could be a sharp-elbowed affair that often seemed more combat than craft.

The number of newspapers soared during the antebellum period, from about two hundred in 1800 to twelve hundred by the mid-1830s. (That number would rise further to more than sixteen hundred by 1840.) Much of that growth stemmed from the nation’s expansion in the frontier West. Newspapers were fast to sprout, but not always profitable. Many were forced to swallow unpaid debt in order to avoid cutting off coveted subscribers, who were sometimes unable to keep up with subscription prices that amounted to $2 to $3 a year. The historian Thomas C. Leonard notes that during the period before the Civil War, many newspapers swapped their publications for products as a way to make ends meet. “Country newspapers announced they would settle bills for crops. Newspaper offices took in flax and wool, cheeses and feathers. Journalists came to accept cattle, hides, beeswax, and rags in payment for the news,” Leonard writes. “Of all American vices, non-payment of subscriptions was among the most egalitarian.” Over the years, Lovejoy would become all too familiar with the financial challenges of keeping a newspaper afloat on the frontier.

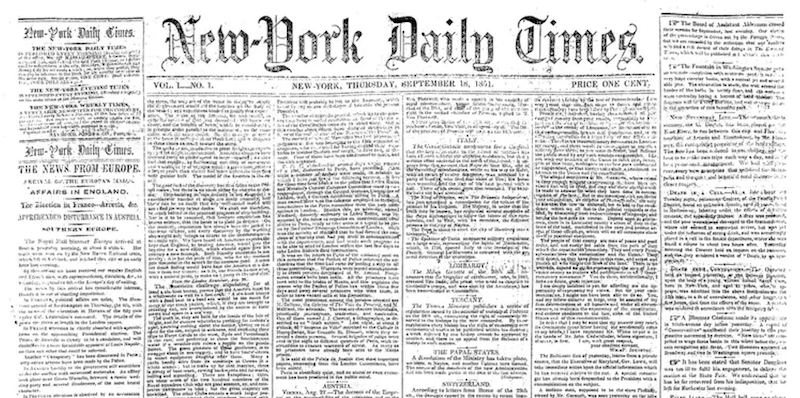

Like Lovejoy’s Observer, nearly all of the newspapers during this era were issued on a weekly basis—daily newspapers were mostly found in big cities, such as New York, that could provide the volume of advertising needed to sustain them. The paper on which newspapers were printed was still made from rags during the 1830s—years before the advances in technology that would allow cheaper wood pulp to be used. And newspapers in this period were big—conventional broadsheet pages measured eighteen inches wide by about twenty-four inches long, requiring readers to spread their arms wide when reading an open paper or learn to fold creatively. (In later years, some papers swelled to dimensions of nearly twenty-four inches wide by twenty-eight inches long.) The papers weren’t thick, though; many contained just four pages.

The number of newspapers soared during the antebellum period, from about two hundred in 1800 to twelve hundred by the mid-1830s.The work of an editor often seemed to require the skills of a clever stock clerk—figuring out how to jam as many items as possible into a limited amount of space. Photographs were still years away from hitting newspaper pages, and illustrations were used almost exclusively for display advertising, meaning that the news pages usually resembled a broad carpet of gray: five or six tightly packed columns of often minuscule type, interrupted by the (only slightly) larger type of headlines. Hair-thin lines acted to separate one article from the next, so it could be quite hard to know where one article ended and another began. Sturdy readers who picked up a newspaper in the early 1800s were on their own to navigate a dizzying mishmash: advertisements, minutes of local meetings, complete texts of windy congressional speeches, hometown editorial columns, and assorted news items, the majority of which came from abroad or other parts of the United States (and usually days or even weeks old).

Newspapers favored foreign and national news and offered scant news about the communities where they resided. Editors packed their pages without apparent regard for layout considerations based on newsworthiness, a concept that had not yet been developed in American journalism. Rather, much of the material that Americans read was in uncooked form, arranged verbatim from other publications onto the editor’s own press alongside whatever other items good fortune had swept to his shores. Newspapers of the early 1800s resembled inside-out versions of their modern-day descendants, stuffing the biggest news into their inside pages. The precious real estate of the front page was reserved for display ads for everything from hats to hardware, plus small notices for professional services—lawyers, shipping brokers, auctioneers—that many years later would be called classifieds.

One reason for the abundance of news from afar was the practice by newspapers of swapping editions with other papers, even those in distant locations in other states. Editors would mail a copy of their paper to their faraway counterparts, who would collect the bundles from US mail coaches and then reprint selected articles in their own papers, usually by attributing the original source of the news items. Editors thus won in two ways: they got notice for their work in other parts of the country, while at the same time gaining a potent and cost-effective tool for gathering news. The exchanges were, in effect, an early (and slower) version of the news collective that would become known as the wire service. Newspaper exchanges played a huge role in fomenting national conversation on seemingly parochial issues—a flood in Virginia could get play in Missouri, for example—and therefore serve part of the broader, unifying function that foreign observers noticed when they looked at American journalism at the time. As Thomas Hamilton put it, the reach of newspapers ensured that “the most remote invader of distant wilds is kept alive in his solitude to the common ties of brotherhood and country.”

Newspapers favored foreign and national news and offered scant news about the communities where they resided.If newspapers of the era succeeded in turning Americans into news junkies, they owed a large measure of thanks to a surprising sponsor: the federal government. Or, more specifically, the US Post Office. An uncelebrated act of Congress—the Post Office Act of 1792—helped bring about a stunning transformation in how Americans communicated by launching a vast expansion in the postal system and providing a cheap way for mountains of newspapers to crisscross the nation in the age before the telegraph. Although the creation of a postal system might seem inevitable in a new country, it took Congress several years after passage of the Constitution to lay out a vision of what would be the biggest function of the central government.

Until then, exchange newspapers were admitted at no cost into the mail stream at the discretion of riders carrying the mail. But in passing the Post Office Act, Congress sided with those who argued that allowing newspapers into the mail on a selective basis created an opening for the federal government to favor one publication—and its political stances—over another. The answer was to allow all newspapers to be sent through the mail, at a nominal cost of a penny for distances under one hundred miles.

The effect of the postal law was to promote a communications revolution that was on par with the dramatic advances surrounding transportation through road and canal building and the steamboat. Historian Richard R. John, who has written about the transformative role played by the postal system in US society, said the number of newspapers sent by mail skyrocketed from 1.9 million a year in 1800 to 16 million by 1830—though still just a fraction of all the newspapers published around the country. By 1832, John writes, the towering heaps of newspapers, in sacks weighing up to two hundred pounds each, accounted for 95 percent of all the weight carried by postal carriers. “By underwriting the low-cost transmission of newspapers throughout the United States, the central government established a national market for information 60 years before a comparable national market would emerge for goods,” John writes.

The federal government, through its postal law, helped make the lowly newspaper editor a force to be reckoned with—and one highly dependent on the regular arrival of the mail sack. (Editors complained bitterly in print when delays in delivery left them bereft of news to publish.) By making it possible for news and essays from one part of the country to appear in another, the mail system served as a binding agent for a nation spreading far beyond its original contours along the Atlantic coast. But the conversation wasn’t always welcome. Later in the 1830s, the Post Office’s crucial role in the flow of fact and opinion would place it in the middle of a debate over censorship, when antislavery activists sought to promote their viewpoint in the South.

__________________________________

From First to Fall: Elijah Lovejoy and the Fight for a Free Press in the Age of Slavery by Ken Ellingwood. Used with the permission of Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2021 by Ken Ellingwood.