How a War Over Eggs Marked the Early History of San Francisco

Egg dishes are a flavor of home. We want them the way our fathers or mothers or grandparents made them. An egg conjures memories of learning to cook for many of us, since making eggs is perfect for teaching a kid. Even if one disdains a straight scramble, the egg is a key ingredient in many comfort foods, including pancakes and birthday cake.

For all these reasons, eggs carry a certain nostalgia. They remind us of paradise lost—the childhood that is done, the beloved elder chef who is buried, the metabolism that once tolerated syrupy breakfast carbs. And nostalgia has power. Would you kill to return to a yolk-kissed moment when a caregiver served up love on a plate? Some men would. And, indirectly at least, some men did during the Egg War of the Farallon Islands.

The Egg War began unofficially in 1848 with the Gold Rush. San Francisco started the year with a mere thousand souls, but over the next twelve months the population rose to twenty-five thousand. The city experienced scarcities of women and of food, particularly protein. Scaling up farms to provide for the local population proved harder than it seemed. Nobody could get large groups of chickens to survive there, and the technical solutions to this problem were decades off. Without chickens, of course, there could be no eggs. And without eggs, there could be no cakes, morning scrambles, pancakes, puddings, or muffins. As Napoleon once put it, “An army marches on its stomach,” and a rootin’-tootin’ army of miners in the Wild West doubly so.

As gold poured into the city, the prices for fresh eggs skyrocketed. Out in the field, a single chicken egg might sell for $3, while in the city that same egg fetched the still exorbitant price of $1. Even without accounting for inflation, $12 to $36 per dozen eggs is ridiculously expensive. If we account for inflation, the miners paid something astounding—more like $427 to $1,282 per dozen. This explains the origins of Hangtown Fry rather well. According to legend, a guy who had struck gold wandered into the El Dorado Hotel in the mining supply camp of Hangtown (so nicknamed for its penchant for stringing up criminals). He threw down a bag of gold and demanded the most expensive meal the chef could make—which turned out to be oysters and eggs. If someone could bring good fresh eggs to San Francisco Bay, he would more than make his fortune.

If we account for inflation, the miners paid something astounding—more like $427 to $1,282 per dozen.By most accounts, the first people to strike it rich were “Doc” Robinson and his brother-in-law Orrin Dorman. Doc, a pharmacist from Maine, had figured out that the Farallon Islands, home to hundreds of thousands of screaming seabirds, might provide enough eggs to finance a new pharmacy. So Doc and Orrin hopped in a boat and set sail for the Farallones, about thirty miles outside of San Francisco Bay.

As a location, the Farallones are pretty cursed; they are the sort of place a third-grade boy would make up to impress and gross out his classmates. Although to call them “islands” is a bit grand—they are jagged rocks of various sizes that stick up above the water. Those rocks are a legendary site of shipwrecks. Since Sir Francis Drake set foot on the islands in 1579, mariners have referred to the group as the Devil’s Teeth, for their appearance, the rough seas that surround them, and their tendency to chomp on ships.

One of the smaller islands is known simply as “the pimple,” a rock six meters tall and sixty-five meters wide, with a whitehead of bird droppings on it. The sea salt blasts the rocks, and white crystals crunch underfoot on some of them. Before the Europeans arrived, the Ohlone people called the Farallones part of the land of the dead, specifically the part meant for the bad, dead people.

If these weren’t enough of a deterrent, great white sharks infest the seas surrounding the islands, which is unusual since great whites tend to only travel solo or in pairs. But around the Farallon Islands, they gather in numbers up to 150 sharks. It probably has to do with the large population of pinnipeds that also populates the Farallones.

Once home to fur seals and sea otters until Russian and Boston fur merchants decimated local populations in the early 1800s, the islands also played home to elephant and harbor seals, as well as several species of sea lions—a veritable buffet for the great whites. The kelp flies, of course, also came to lunch on the pinnipeds. And kelp flies number among nature’s vilest creatures. I will let journalist Susan Casey explain. For unfathomable reasons, she spent weeks on a rickety yacht moored offshore of the largest island in the 2000s while reporting for her shark book titled after the archipelago:

They were at their peak now, a carpeting plague, crawling up pants legs and down shirt fronts, overwhelming a person’s every moment outside. And these flies were not the cleanest insects—their preferred habitat is the inside of a seal’s anus. The anus flies spent their time in one of three ways: tormenting us, tormenting the poor seals who had to house them in such an inhospitable place, and copulating with abandon in giant fly gang-bangs. This morning I’d counted a vertical stack of thirteen flies.

I personally draw the line at anus flies.

Into the tumultuous, shark-infested, kelp fly-ridden water, Doc and Orrin sailed. They landed on the largest rocky outcropping, which is less than a fifth of a mile square. There, they came face to face with the overwhelming fact of life on the island—its birds. Hundreds of thousands of seabirds—gulls, cormorants, auklets, puffins, petrels, and most important, the common murre. These shrieking, squawking birds, packed shoulder to shoulder among the cliffs, laid great volumes of eggs onto masses of weeds and likely comprised more than half a million nesting pairs. Importantly, the common murre outnumbered the other seabirds. A type of guillemot, the common murre dresses all in black, save for its white belly.

Each year, female murres lay a single pear-shaped egg with a tough shell. The eggs have background colors in the greenish blue range, with darker brown-black pencil squiggles and dots atop. Roughly twice as large as a chicken egg, with a bright red yolk and a white that stays translucent when cooked, murre eggs made a fine substitute in baked goods. When not eaten absolutely fresh, though, they leave an aftertaste of old fish. Eat a thoroughly bad murre’s egg, and rumor had it that you’d spend three months getting the flavor out of your mouth.

Doc and Orrin scrambled up those slippery, excrement-covered cliffs and filled their boat with eggs. On the harrowing journey home through rough seas, they lost almost half their booty. But when they arrived in San Francisco, their half boatful of eggs fetched a small fortune of $3,000 (something like $100K in 2020 money). Doc Robinson used his share of the profits to build a pharmacy and the Drama Museum, a theater where he delighted locals with his impressions of New Englanders. He went on to become a pillar of the nascent theater community. But the trip had so terrified him and Orrin that nothing could persuade them to return. Word of their profits, though, spread quickly. The egg rush had begun.

Within a week, eggers swarmed the Farallones seeking their fortune. One enterprising collection of six men promptly formed the Pacific Egg Company (also known as the Farallon Egg Company, or simply the Egg Company) and, in keeping with the land-grab ethos of the time and place, staked their claim on the largest island. They fought off their foes, erected some outbuildings, and soon established brutal methods for gathering eggs. First, they’d rampage through one section of the egg fields, breaking every egg in sight, which ensured the freshness of the next day’s harvest.

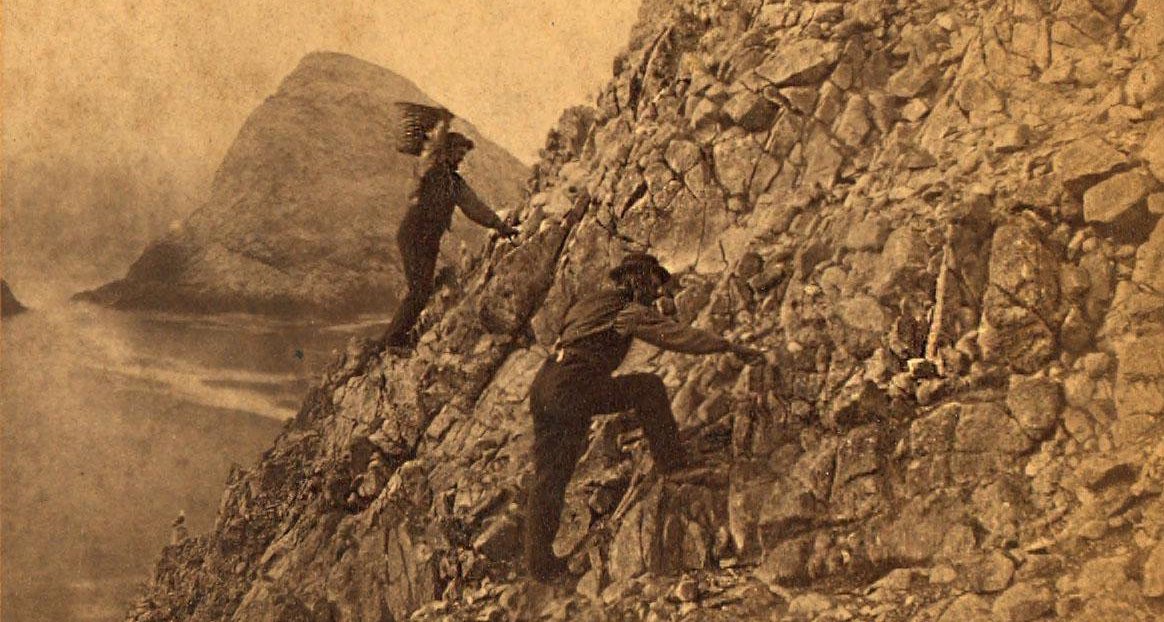

Their crews had specialized gear—rope-soled shoes, often with spikes driven into them, to help them gain purchase on slippery cliffs. The egg man’s uniform also included climbing ropes and special vests made of flour sacks with a drawstring waist and holes cut for the head and arms. Eggers deposited their cargo into a deep slit in the vest’s neck, which allowed them to carry up to eighteen dozen eggs without a basket. On the cliffs, keeping hands free was key. When fully laden, the eggers resembled lumpy Santas and would return to a collection point at the base of the cliffs. They would kneel deeply over a basket, almost as if praying, and let the thick-shelled eggs pour from their chests.

The work required desperation or nerves of steel, probably both. The company employed up to twenty-five men at a time, often new immigrants with little to lose. The treacherous egging season ran from May to mid-July. A simple slip on the cliffs could send a worker into the shark-infested brine. And then there were the gulls.

ccording to an 1874 Harper’s article on the eggers, “These rapacious birds follow the egg-gatherers, hover over their heads…. The egger must be extremely quick or the gull will snatch the prize [the egg] from under his nose. So greedy and eager are the gulls that they sometimes even wound the eggers, striking them with their beaks.” To avoid frequent scalp injuries, many of the eggers carried clubs, which they swung around their heads.

With the Pacific Egg Company in control of the largest island, local fishermen and other fortune-seekers ventured out to the smaller boulders. A local newspaper ran a story on one such pair that ended up stranded on a rock for six weeks in 1899. Stormy seas foiled at least three rescue attempts, leaving the men to survive on raw eggs and the meager supplies rescuers could land. Returned to safety, one of the emaciated castaways told the local newspaper, “I will never again be able to look at a murre egg without disgust. We have had several fights with the sea lions.” A dramatic drawing of a man with a bat fending off a ferocious pinniped accompanies the story.

Throughout the 1850s, the Farallones’ yearly egg season brought armed struggles as the Pacific Egg Company vied for control of its veritable gold mine. It fought off gangs “armed to the teeth,” according to an 1859 Alta California article. Battles raged on land and sea, as hijackers attacked boats ferrying eggs to the mainland.

One group of rival eggers spent several days hiding in their boat inside Great Murre Cave beneath the largest island, where guano continuously rained down on them and the ammonia buildup killed several men. A government force sent into the fray in 1860 found themselves so outnumbered and outgunned that they “thought it prudent” to return home without engaging.

Battles raged on land and sea, as hijackers attacked boats ferrying eggs to the mainland.If it wasn’t rival gangs of eggers testing the egg company, it was the government. In 1855 the US government seized the land and built a lighthouse there. It refused to recognize the egg company’s claim to the land but allowed it to keep up its rapacious methods so long as it didn’t interfere with lighthouse business.

The federal government fixed pay for all lighthouse keepers at a paltry $450 to $600 per year. Not bad if you lived in the East, but in the inflation-happy epicenter of the Gold Rush, domestic servants could earn nearly that in a month, plus room and board, and all without having to live in a nightmare hellscape of guano and bird shrieks. Nerva N. Wines, the first lightkeeper, who served from 1855 to 1859, became a stockholder for the egg company and let them run amok so long as he received his dividend.

His successor, Amos Clift, had a better scheme. Clift had taken the job for the express purpose of commandeering the eggs. As he wrote in a letter to his brother, “If I could have the privilege of this egg business for one season, it is all I would ask [and] the government might then kiss my foot.” Clift boldly leased egg-gathering rights to various parties and remained the keeper through the season of 1860, when the Lighthouse Board fired him for corruption. Without Clift managing the many competing parties, the conflict heated up.

It started off with the egg company posting signs barring the lightkeepers from certain parts of the island. Next, eggers busted up government roads, and an armed group captured four lightkeepers and tried to eject them from the island. Later that same year, someone assaulted an assistant lightkeeper. The situation had gotten more out of hand than usual, and the government struck back.

The regional superintendent of lighthouses, Ira Rankin, had a pragmatic streak and realized that so long as the egg rights to the land were up for grabs, the assaults, stabbings, intra-egger battles, and graft would continue. So he decided to crown the original egg company ovary overlords of the Farallones and to hell with whether it was technically legal. (On paper, at least, the land belonged to the US government.) And Rankin would support the egg company using government power.

A freelance egger named David Batchelder took powerful exception to this move and made repeated, armed attempts to take the island with increasingly large numbers of men, Italians, a detail the papers loved to include. During the start of the 1863 season, he and his men built a house and a stone fortification on the island. Rankin responded with an armed customs ship that laid siege to Batchelder’s operation. The government removed four men, five shotguns, a rifle, and assorted other weapons. But Batchelder was not easily deterred.

Two weeks later, he returned with at least thirty men, who captured several Pacific Egg Company employees. Again, the same customs ship arrived and landed three boats of men to round up the egg rebels, plus their arsenal of twenty-one firearms. At some point, Rankin realized that a few lightkeepers must be in league with Batchelder, so he sent a sternly worded letter threatening to fire anyone assisting the upstarts. Rankin also ordered the customs ship to patrol nearby waters, questioning any boat headed to the Farallones and boarding it if necessary.

Batchelder was rumored to be gathering forces for another try. On June 3, 1863, three sloops dropped anchor off the coast of the main island. They contained Batchelder, twenty-seven armed men, and a four-pound cannon. Isaac Harrington, the egg company foreman, met the boats at the landing, a wooden derrick built over the inhospitable shoreline. He howled across the waves that the rebels would land “at their peril,” and Batchelder yelled that they would come ashore “in spite of hell.”

Everyone spent a tense night, the egg company men camped on the landing and Batchelder’s men carousing in their boats. At daybreak, the rebels sent one boat in for a landing, and everyone opened fire. When the gunshots and feathers settled twenty minutes later, one of the company men was dead with a hole blasted through his stomach, and Batchelder’s men beat a hasty retreat, leaving a sloop behind. Five of Batchelder’s men had injuries, including one shot through the throat, who died at a hospital a few days later.

After Batchelder’s grand defeat, the rivalries among egg gangs died down, though tensions between the Pacific Egg Company and lightkeepers remained high for several more decades until an 1881 executive order barred commercial collection on the islands. Twenty-one soldiers arrived to evict the egg company from the land permanently. Informal egging and selling by the lightkeepers continued till the end of the century but eventually ceased as the rising supply of chicken eggs made it far less profitable.

The Farallon egg trade lasted for a half century, with tragic ecological consequences for the birds. Estimates vary from source to source, but at the beginning of the egg rush, the company likely shipped around 900,000 eggs per year. Fifty years later, that number was closer to 150,000 eggs shipped, a sixth as many. The unchecked smashing and stealing of murre eggs had a predictable effect, decreasing the murre population by about 95 percent, from a high of 400,000 to 600,000 before egg gathering to a lean 20,000 birds at the trade’s conclusion.

Later environmental degradation—multiple oil spills, shipping lanes, falling numbers of tasty sardines, to say nothing of an underwater nuclear waste dump—further diminished the number of murres to a mere 6,000 by the 1950s. Since then, thanks to conservation efforts, numbers have greatly recovered, hitting 100,000 in 2000 and 250,000 to 300,000 in 2020.

*

Humans have done far worse in pursuit of eggs. Before Doc Robinson retrieved the first boatload in the Farallones, before the Gold Rush entirely, the great auk flourished. A large, docile, penguin-looking bird, the auk was a member of the common murre’s biological family. Like murres, great auks congregated in large groups—a move that would turn out to be foolish—to lay their eggs on the bare rock of sea islands. Black with white bellies like the murre, this oversized, flightless cousin bred on rocks off the coast of Greenland, Newfoundland, Iceland, Massachusetts, and Scotland.

They had the minor misfortune of moving and breeding slowly—females laid only one egg a year—and the greater misfortune of soft feathers, tasty flesh, and fat that made a fine fuel oil. Laws going back to the 1550s tried to protect the birds, but they proved too easy to catch and too useful. One of the sadder passages I’ve read is the 1794 description of an auk hunt by Aaron Thomas of the HMS Boston:

If you come for their Feathers you do not give yourself the trouble of killing them, but lay hold of one and pluck the best of the Feathers. You then turn the poor Penguin adrift, with his skin half naked and torn off, to perish at his leasure. This is not a very humane method but it is the common practize. While you abide on this island you are in the constant practice of horrid cruelties for you not only skin them Alive, but you burn them Alive also to cook their Bodies with. You take a kettle with you into which you put a Penguin or two, you kindle a fire under it, and this fire is absolutely made of the unfortunate Penguins themselves. Their bodies being oily soon produce a Flame; there is no wood on the island.

The human cruelty blows me over—to skin animals alive or boil them alive on a fire made of their fellow birds. It’s a vision of hell.

By 1800, many of the great auk habitats had been destroyed. The scarcity of great auks made their eggs more valuable to oologists, who sent collectors out to snatch eggs and skins, which further decimated their populations. In 1844, three Icelandic hunters visited Geirfuglasker, a coastal island, to secure some specimens for a merchant. On June 3, they found the last known nesting pair of great auks, strangled them, and deliberately smashed the last egg with a boot. One of the hunters later described the scene to a researcher: “I took him by the neck and he flapped his wings. He made no cry. I strangled him.”

As I remember the large, old great auk shells in the cabinet, I think perhaps the birds are not the foolish ones after all.Early in 2020 I visited a collection of great auk eggs at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University. Collection manager Jeremiah Trimble, red-headed and with a hint of stubble on his cheeks, had an obvious love of the natural world; he lit up when I asked him about birding. He ushered me into the large windowless room that hosts the museum’s enormous collection of nearly 500,000 specimens of eggs and skins. Taxidermied birds perched atop the grayish cabinets that packed the room.

I had a list of eggs I wanted to see—the glossy iridescent green-blue of the South American tinamou inside a clear plastic box within its drawer; the Tic Tac–sized hummingbird eggs, displayed inside nests that were, as Trimble explained, held together with cobwebs, like some fairy house. I saw globed white owl eggs, and the beautifully pointy and speckled egg of the common murre, including one collected in the Farallones. The egg of the elephant bird of Madagascar had recently been on display and lived in a cabinet. Such birds once laid the world’s largest eggs—the size of watermelons. Though historians now debate the cause of their extinction, which occurred sometime between 1000 and 1200 CE, one theory suggests that humans simply ate them to death.

After fitting the enormous beige-brown balloon into its box, Trimble showed me a very special cabinet on the other side of the room: a drawer of extinct species. He showed me the oblong golf ball of what was the United States’ only native parrot species, the Carolina parakeet. Down the row from it lay a small, glossy white egg from the passenger pigeon, a species too tasty for its own good. Perhaps the world’s largest collection of great auk eggs lay nearby, more than a dozen of them, the supersized version of the common murre eggs.

Though I try to be open-eyed about the depravity of the era of exploration, I confess I do feel nostalgic for it sometimes. Not for the bad medicine or the narrow range of roles women and people of color were allowed to play in public life, but for the global sense of adventure and for the natural world that has been lost. How wild that the United States once had an exotic parrot species, with its orange head and teal body. I wonder about the people back then: did they count themselves lucky to walk the Earth at the same time as the Carolina parakeet or the great auk? Or did they simply see birds as commodities for exploitation or as mere scenery?

Peeking inside the drawer sparked a mix of emotions: illicit delight in seeing something rare mixed with solemnity since all that survives of these species are these remains locked in basement drawers. Of course the Victorians did not know how lucky they were to walk the Earth with the Carolina parakeet any more than I knew, when my father-in-law came over to play with my baby one morning, laid him on the carpet floor, and said, “Coochie coochie coo—you’re not going to see any white rhinos, are you? No, you’re not” to my child on the day the last male white rhino died. The white rhinos are lost. There are no more elephant birds. There are no more night herons or dodoes or Reunion ibises.

I thought of that sepulchral drawer again nearly a year after my pilgrimage, when the US Fish and Wildlife Service announced the extinction of twenty-three more plants and animals, including Bachman’s warbler, a symphony in yellow, black, and moss-green. We have made the same mistakes over again, and as I remember the large, old great auk shells in the cabinet, I think perhaps the birds are not the foolish ones after all.

__________________________________

Reprinted from Egg: A Dozen Ovatures by Lizzie Stark. Copyright © 2023. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.