Building an Ancient Egyptian Stool

I found this ancient Egyptian stool on the British Museum’s website in early 2020 and fell in love with it. A couple of things pushed me to make a copy – curiosity about the execution of its joinery and a desire to own it, sit on it, and see how it holds up over time.

I’d planned to visit and photograph the museum display but COVID cancelled my London vacation and I had to make due with the website images. Thankfully, the object’s Museum page has excellent pictures, measurements and the image viewer allows you to zoom in quite close. The stool’s catalogue number at the British Museum is EA2476.

EA2476 was purchased in 1835 from a sale of the estate of Henry Salt, a British painter, diplomat and collector. This sale of Egyptian tomb goods represented only one of several large hauls he’d amassed and sold off during his 47 year life. Busy guy.

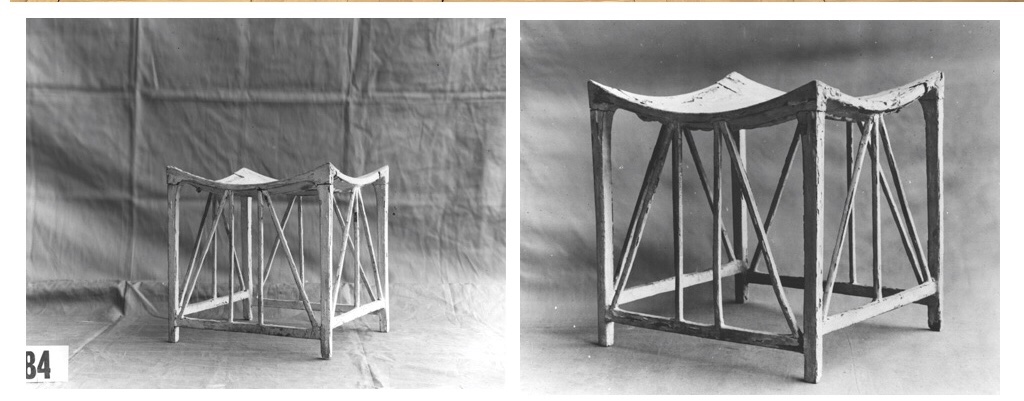

I did some online image research and found a number of very closely related stools from 18th Dynasty Theban tombs. There’s a very similar stool from the Tutankhamen tomb among the Harry Burton photos archived at the Griffith Institute at Oxford University. The Institute has a number of collections documenting that excavation and many other resources worth exploring. I was amazed to find they sell contact prints made from the large format negatives in their collection and I purchased a couple of this particular stool – object 84. Compared to EA2476, it’s a little more gracile, with a leather seat stitched to an open frame rather than curved wooden slats but it’s nearly identical otherwise and the photo is a useful view.

There’s another stool sitting a few feet away from where object 84 was found. It appears to be made of reed and looks like the inspiration for the wooden versions. Lumber was an expensive import product, so I’m guessing this sort of reed furniture was more widely used in ancient Egypt than it’s representation in upper class tombs might suggest.

Next instalment touches upon EA2476’s influence on early/mid 20th century furniture design, then gets ready for the build.

DISCLAIMER #1 – On the history of design, consider me an “internet expert”.

Lots of googling suggests that Liberty & Co retailed versions of various Theban stools from the late 1880s into the 1920s. Swiss and then Danish designers started around 1900 and carried on through the 1950s. I’ve dumped some of my auction site and lifestyle aggregator screen grabs into this image and will limit myself to a few general comments…

These stools follow the basic form of the Theban originals but weren’t intended to be exact copies. They would have required some hand work but were designed to exploit the efficiencies of machines found in production workshops from the late 1880s up to this day. The most common modification was to move the connection of the seat frame/leg joint down so the bottom surface of the wood block could serve as a reference face, making it simple to register a dowel drilling guide instead of cutting an oddly recessed mortise and tenon joint.

Now that we’re talking about particular bits of the construction, let’s quickly nail down our terms…

DISCLAIMER #2 – I won’t be providing any clean measured drawings, only napkin sketches.

So we’re ready to start marking out and cutting up wood. In the next instalment we’ll talk about tools and get the woodworking underway.

I’m not using period tools.

Geoffrey Killen covers Egyptian tools extensively in his book Egyptian Woodworking and Furniture. The 18th Dynasty woodworker’s handsaw is functionally the same as a modern one, so I’ve used a panel saw and back saw. As far as I know they didn’t have bow saws or coping saws, so all my inside curves were made by sawing multiple straight kerfs, splitting off the segments and then paring with a gouge down close to the final surface. The adzes in the picture would have been used to straighten all the flat surfaces but I stuck with hand planes because I didn’t want to lose any fingers. I was more concerned with staying true to the procedures than exactly replicating techniques or textures. It’s been suggested by G. Killen that the adzes could’ve been held in a plane-like way for final smoothing. The Egyptians also would have sanded with flat or curved stones to a final smooth finish. I work in my apartment and for health reasons try to minimize my use of sandpaper. I used some coarse rasps for rough work on the seat underside but switched to cabinet scrapers for the final shaping.

So I started out by grabbing the side view from the Museum site, consulted the dimensions listed in the data tab and overlaid a grid with my iPad’s Procreate app. I set it for 2cm per square. I used an online calculator to work out the radius of the seat curve given the length of the arc and the depth of the central “dip”.

I took that info and constructed full size views of the end & side on paper.

The full size drawing was a worthwhile step. Later, I was able to lift and transfer a lot of the measurements and angles directly from it with dividers and bevel squares. Just as importantly, the process helped flesh out my understanding of the intersecting volumes.

I used cherry scraps from a bed frame project for the roughly 3”x2” thick seat sides. The top and inside were most critical to keep flat and square but I made the outside a reference face as well because I’d be marking the leg sockets on it.

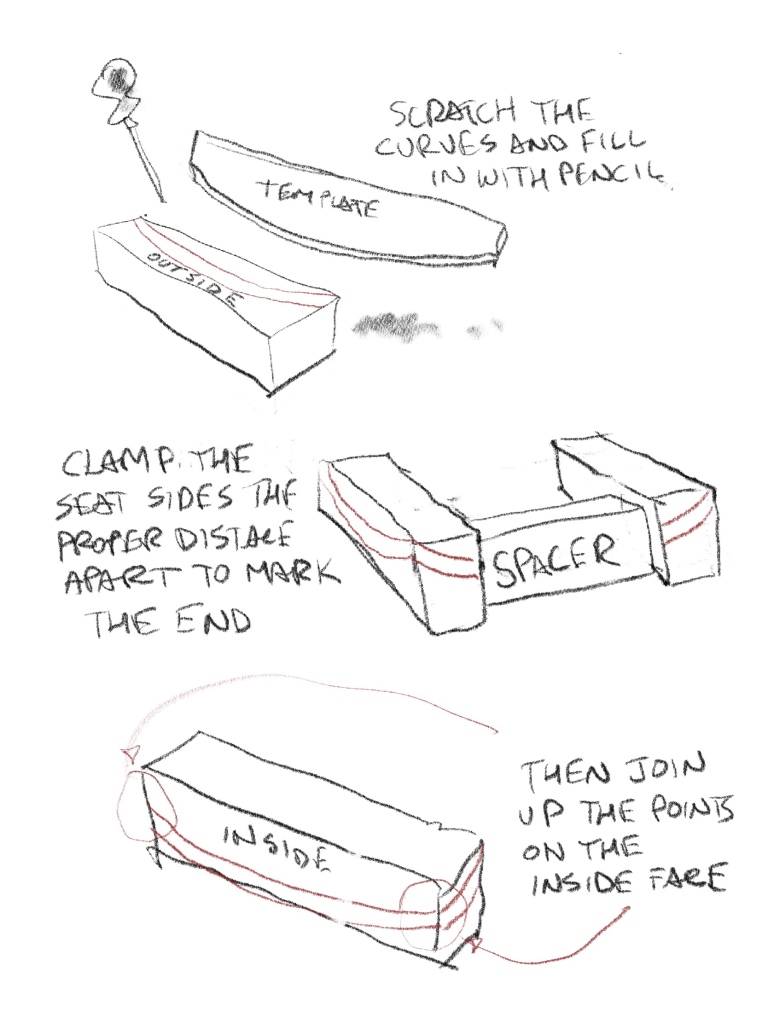

First I marked and cut them to the overall lengths*. Next I made myself a radius template from 1/8” plywood and used it to draw a curve connecting the outside top corners of the rough block. Then I set some dividers for the seat thickness, pricked a few marks to line up the template and repeated the line about ½” lower. I spaced the two side pieces an appropriate distance apart to get the curvature on the ends right. I found it best to use a scratchawl to trace the template. An incised line is easier to register other tools into and more durable than graphite.

* there’ll be a wrap-up post where I describe how I’ll do some processes differently next time. One thing will be to leave the side pieces over length until after the glueing/pinning.

The seat contour looks like part of a sphere but is actually a double cove. One circle sweeps along the circumference of another. The important thing here is that the circles are all vertically oriented, which allows us to plot them on the vertical surfaces of the frames and on the slats too, since their edges will all be vertical.

I assumed the same radius for both circles and it turned out to look correct when I eventually got to see a straight-on end view.

Let’s talk about wood bending.

There won’t be any wood bending.

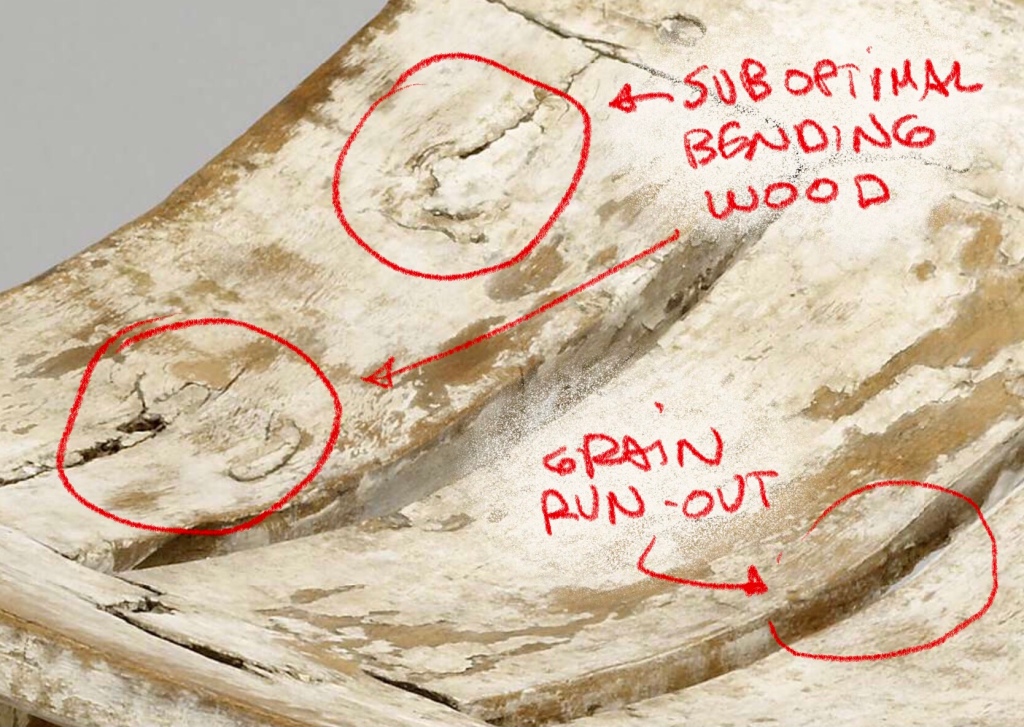

The Techniques field of the object data tab says “steamed(?), bent(?)” but I can make a case against that. The wood under this paint looks pretty knotty in spots and there’s grain and cracks that don’t align with the surface (called run-out), both of which would make it hard to steam bend ½+ inch thick slats without breaking.

DISCLAIMER #3 – I won’t waste pixels typing out “I think”, “possibly” “I speculate” “in my opinion” but consider it implied.

There are are examples of Egyptian steam bent pieces with small tight knots though, so it’s possible to bend it butthe clincher for me is the shouldered tenons on the end of each slat. Generally, bent wood meets up with the rest of any hand-made object by being supported with dowel-type structures or by being inserted into a slot with only a simple shoulder (like on a rustic ladder back chair). Trying to mark and cut 12 closely spaced tenon shoulders on steam bent pieces of wood, that will fit tightly against two flat surfaces, keeping those two flat surfaces rigidly aligned and perfectly parallel to each other?…it doesn’t seem like an efficient use of shop time and I can’t believe it would be standard procedure if you had to bang these out for a living. I stood my 180 lb weight on the middle slats of my cherry replica and it felt solid even when standing on one foot, so cutting the curves from straight-ish grained boards works fine. To get all those tight tenon shoulders (by hand) you need to start with accurately squared up stock.

We’ll look more closely at the stool’s construction in the next instalment.

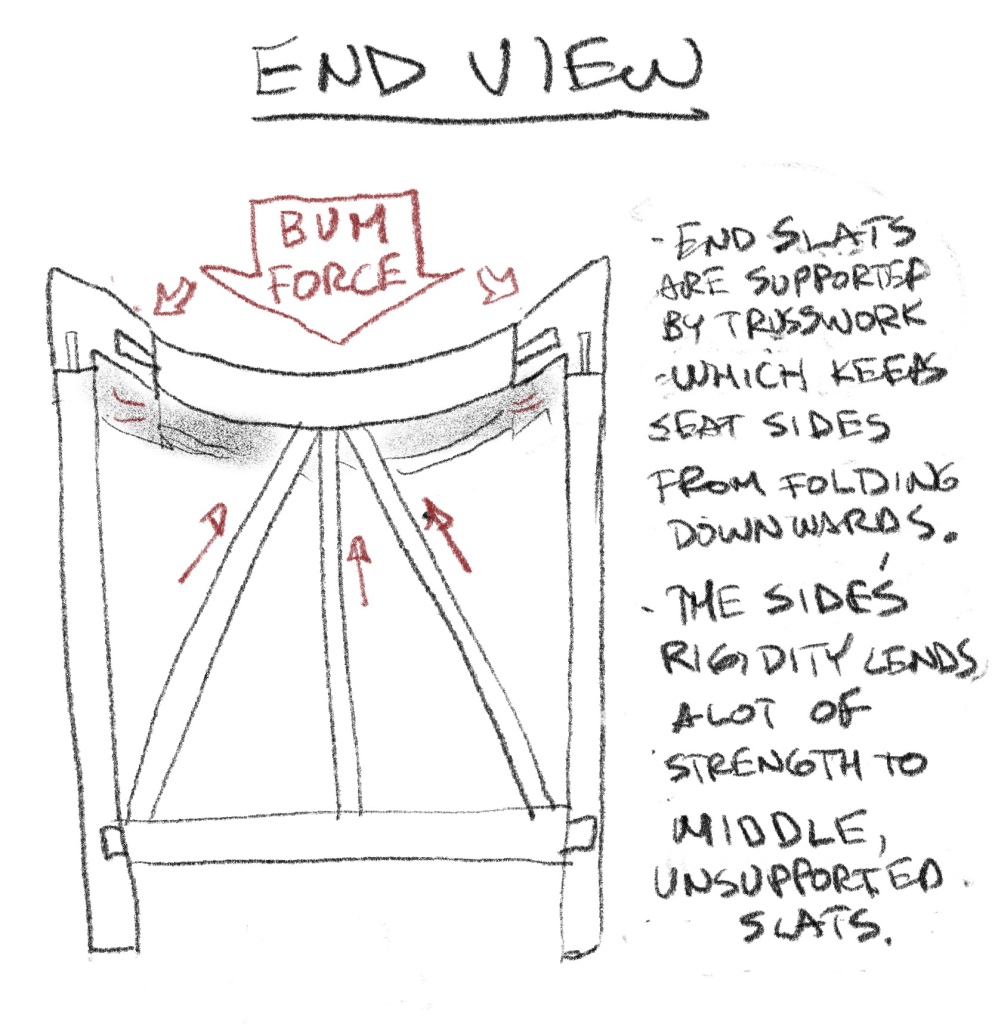

I’m going to step back from the marking out of wood pieces to talk about some of the seat joinery and the likely reasoning behind it. Most of the joints seem less robust than you’ll find in European woodworking. Everything about EA2476 has been pared down to the absolute minimum and all this fragile joinery works together as a seating “system”.

…

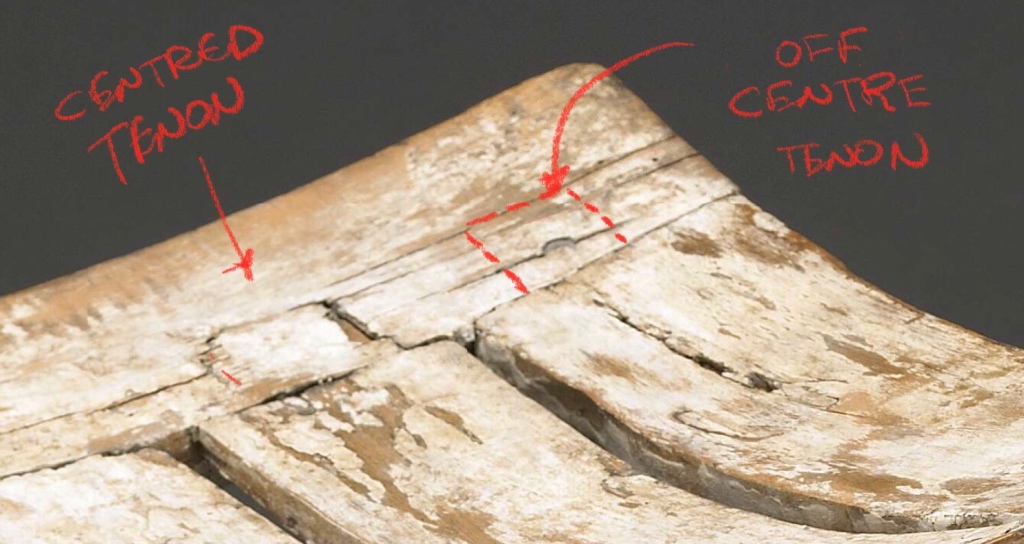

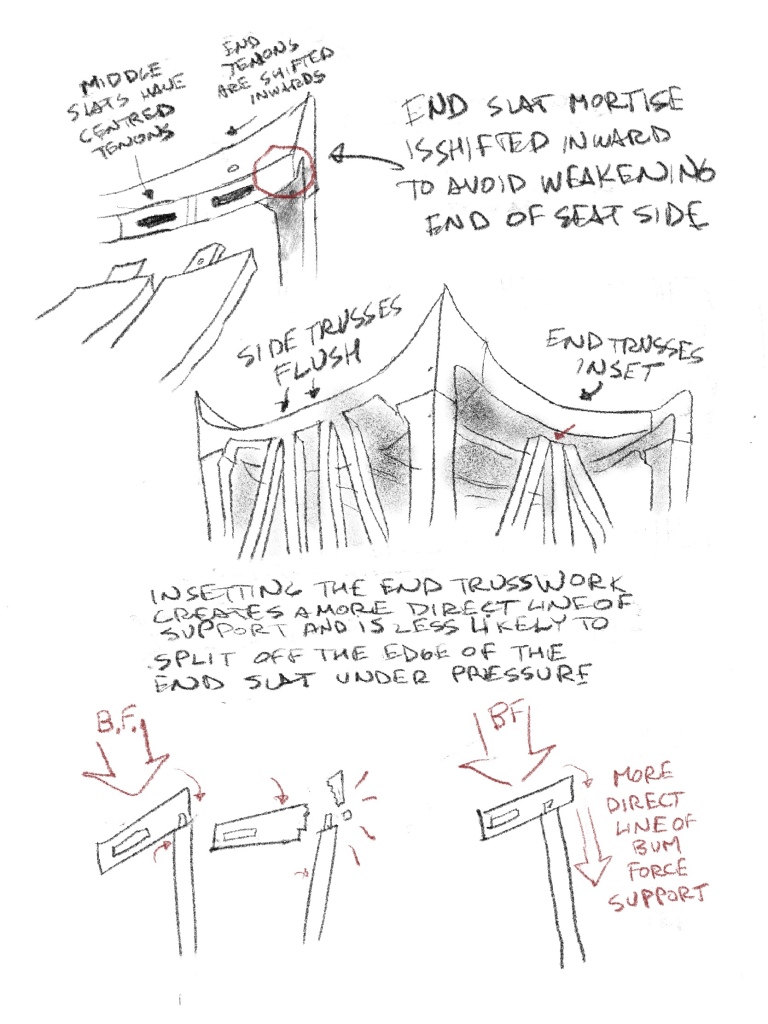

Judging the centre of the tenons from the position of the pin holding them, it’s apparent that the end slats have their tenons set away from the outer edge.

This is done to avoid having a side frame mortise too close to the corner (which would make it very fragile) but it introduces a new problem – the outside edge of the seat slat has less support and is liable to rotate downwards.

To remedy this, the end truss work is inset enough to be more “under” the slat and perpendicular to the rotation. If it were set flush to the edge (like the side trusses are) it might be liable to split it off.

So back to cutting wood…

I marked out the leg sockets and cut them away. At the bottom of the cut, the saw barely touch the bottom inside edge. I worked out the seat side thickness on the drawing to line up like this but until receiving a straight on end view photo after the build, I wasn’t certain my side thickness was correct. It’s one of those efficiencies of design that only come to light when you’re building something.

The dotted pencil lines on the right hand piece show what I sawed away to get closer to the bottom finished shape. It’s best to leave some “meat” on at this stage because the curvature midway between the edges is easy to accidentally cut into. I brought this closer to it’s finished shape than needed because I wanted some reassurance the shapes were working together. Leaving more flat sides makes clamping/work holding safer and easier.

I marked out the mortises next. I drilled them using this simple guide block, both for the correct angle and as a depth stop. Chiselling the waste followed.

They’re all a bit over an inch deep. The mortises on the near end became a little wider than originally planned but it don’t think it’ll be a problem.

Next instalment we’ll be making the slats.

This is starting to feel like a lot of steps.

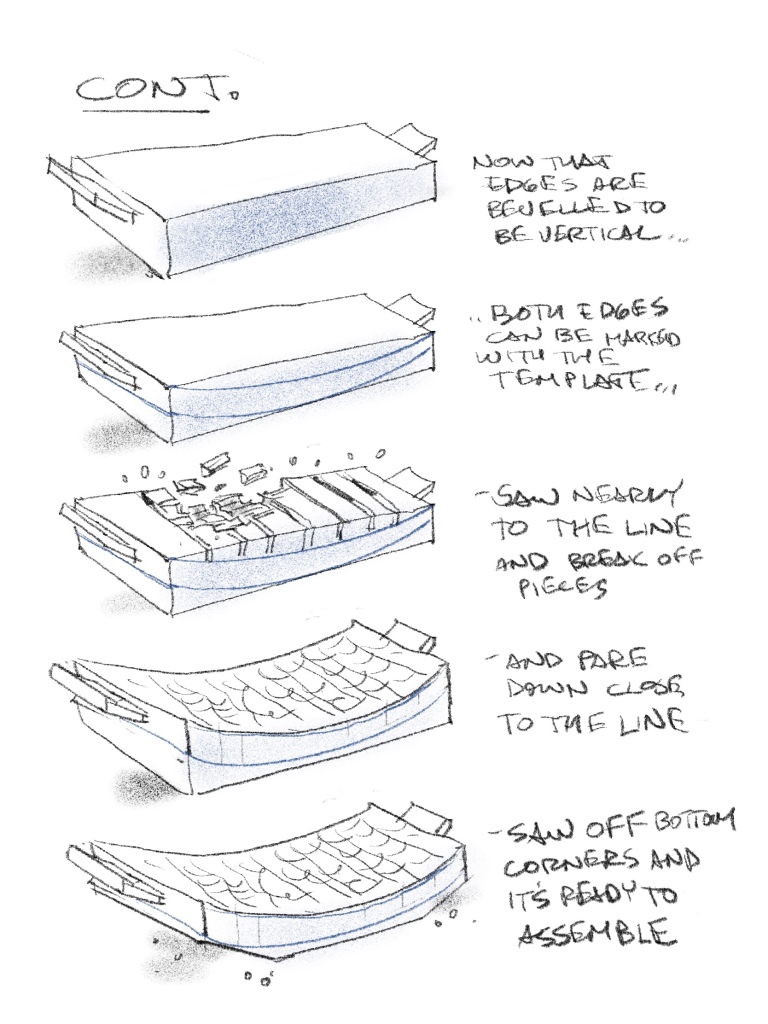

Essentially you’re going to start with a squared up piece for each slat, wide enough to encompass the shoulder contact outline and also thick enough to allow for the belly of the curve. There’ll be 3 different widths needed to make up the 6 slats. You want to mark the tenon shoulders off of one common reference piece to make sure each slat is exactly the same length.

If we orient it like it’ll be in the seat frame, the beveled edge becomes a vertical face and now the template can be used to mark the curves.

So back to “real life” for a test fit.

You can see the slats are all at various stages of completion. Everything was disassembled to continue the rough shaping. The bottom sides of the slats were done with a block plane.

Another test fit with the legs added.

The legs bottom ends have been squared narrow for executing the stretcher mortises. They begin to taper slightly wider above that point.

I left 4 sections of the top surface intact so that I’d be able to lay it flat on the table during glue up and know that it wasn’t twisted.

After glue up, the bottom side of the seat is ready to be final shaped with a rasp and scraper. All the curved lines that were scribed around the seat and slats are still visible and serve to guide the final shaping.

The top side was done with this tiny compass plane (it has a convex sole) and a curved cabinet scraper. A bigger plane would’ve been easier on the fingers.

The seat now has it’s finalsurface. The legs have their final shape too but haven’t been glued yet.

It’s starting to look like EA2476.

Next instalment is the lattice bracing and it’ll be done.

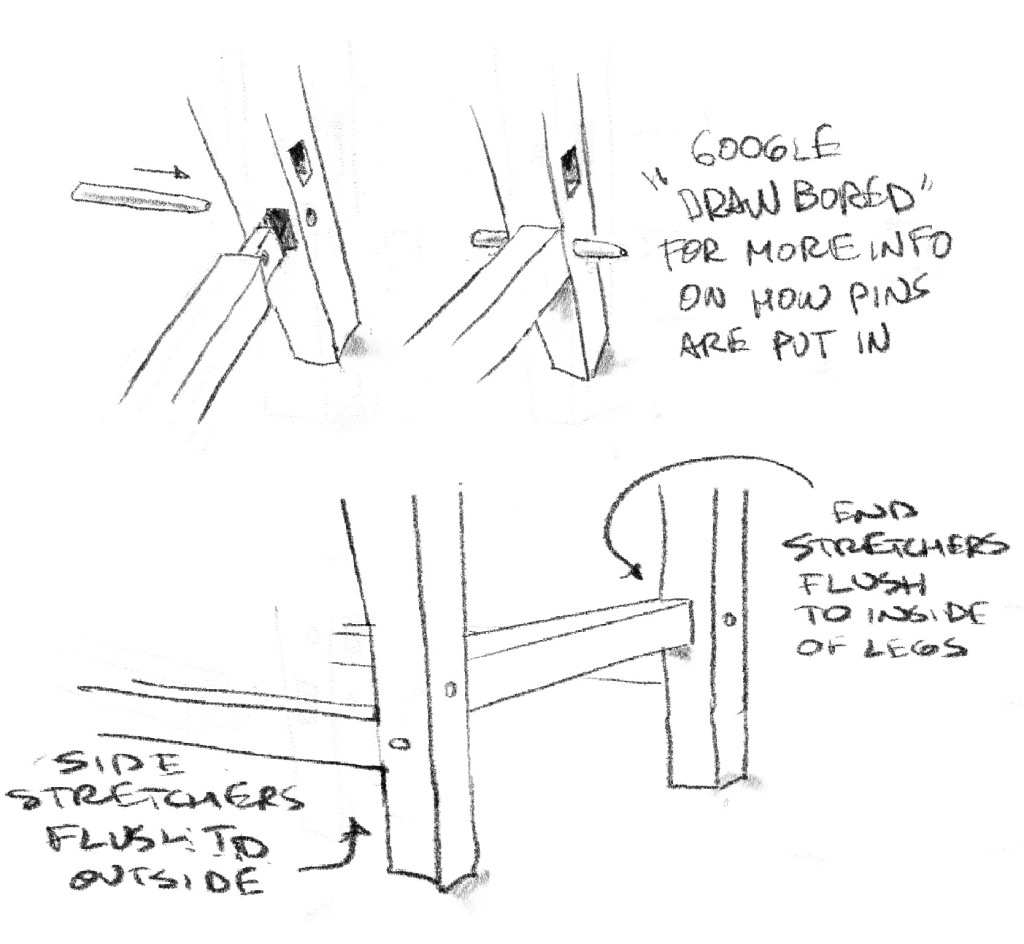

The mortises of the stretchers are off-set vertically to preserve strength in the leg. If the leg were thicker, it would be possible to have them on the same level. The side stretcher is flush to the outside while the end stretcher is flush to the inside.

The truss assembly worried me a lot when I was mentally rehearsing this build. The vertical trusses are straightforward – they can be measured and cut while the stool is dry fitted together. If their length is a tiny bit off, it’s only cosmetic. The diagonals are another story. They’re trickier to fit and if the length is off by the tiniest amount, it’ll throw the stool slightly out of square. With 8 diagonal struts, there’s a real danger that tiny errors could compound, only becoming apparent during glue up as the pins are being driven home. At that point I was feeling stumped.

Geoffrey Killen made a very useful observation about EA2476 on pg 44 of Egyptian Woodworking and Furniture “Some of these (lattice braces) are tenoned into mortises in the horizontal elements while others are simply wedged into position.” I’m not sure exactly what he meant by “wedged” in this instance but it got me thinking…

Disclaimer #4 – without an x-ray I can’t be certain but I feel the following is reasonable speculation.

I’ve seen photos of cabinets on legs with dowelled lattice work and it appears the bottoms of the diagonal trusses are just pressed into notches. Many of the ancient lattice stools have their diagonal trusses connecting to the stretcher at a peculiarly uniform distance from the leg. I think the gap might be there so that a stub tenon can be slid into a mortise. In use, there’s a tendency to bump your heels against the stool’s sides and I think this tiny tenon will do a lot to keep the diagonals in place.

So here it is glued and pinned, with the vertical trusses in place.

With it now perfectly solid and square, I was able to leisurely tweak all the diagonals for a good press fit without introducing any excessive strain on the structure.

This was important because they work in compression, and in opposition to each other. I glued them in with gesso. There are x-rays of joinery inside an Egyptian chair on the Brooklyn Museum site that used a hide glue/calcium powder mixture (gesso) as a gap filling glue. With a subsequent layer of gesso and paint overall, they feel pretty secure.

Finished…

Now we finally get to see how EA2476 would’ve looked as it left an African workshop more than three millennia ago.

It feels very sturdy yet it’s pliable enough to settle flat on an uneven floor without making any creaking sounds. I’m a little over 5’10” and feel it was made for someone my height or slightly taller. I’d be curious to know if 38cm is a standard height for this type of stool.

Stay safe and look after each other.

Paul Bouchard

I’m very grateful to several people for their kind assistance and encouragement (in the middle of a pandemic):

Dr Francisco Bosch-Puche, Archive Curator at the Griffith Archive, Oxford University

Marcel Marée, Assistant Keeper of the Dept of Egypt & Sudan at the British Museum

Harry DeBauche, Project Object Conservator at the Brooklyn Museum

…also, whoever took the object pictures for the British Museum’s website did a fantastic job.

Finally, my deepest admiration goes out to the Egyptian craftspeople who developed and executed this beautiful design so incredibly long ago.

[ comments ]